Listening Through Time: Integrating Ancestral Memory in Education and the Workplace

- Lisa Dawley

- Jul 1, 2025

- 6 min read

For the past three years, I had the amazing opportunity to co-PI Project eSPAC3, a National Science Foundation initiative designed to teach spatial, coding, and design skills to youth through immersive, culturally grounded experiences. At its heart was a Minecraft map where students and families traveled through time and learned to code and build in a Mexican-inspired environment, complete with an extended family, pyramids, a cultural plaza and church, a modern mercado, an auditorium, and more. We witnessed far more than digital engagement; it was ancestral memory in motion.

Parents who had emigrated from Mexico shared vivid stories with their children: how the cathedral bells sounded at dusk, which corner their grandmother used to sell tamales, how festivals lit up the plazas, and a street where a mother grew up. Most of the children had never visited Mexico, but through storytelling, cultural architecture, and emotional resonance, they began to reclaim a sense of place and lineage. The project affirmed what many educators intuitively know but rarely name: learning deepens when we honor the invisible threads that connect us across time. Gonzales et al refer to these threads as "funds of knowledge," the historically accumulated cultural knowledge, skills, and experiences that families and communities possess and use in everyday life, often undervalued in formal education but rich in learning potential, central to identity, resilience, and adaptive learning.

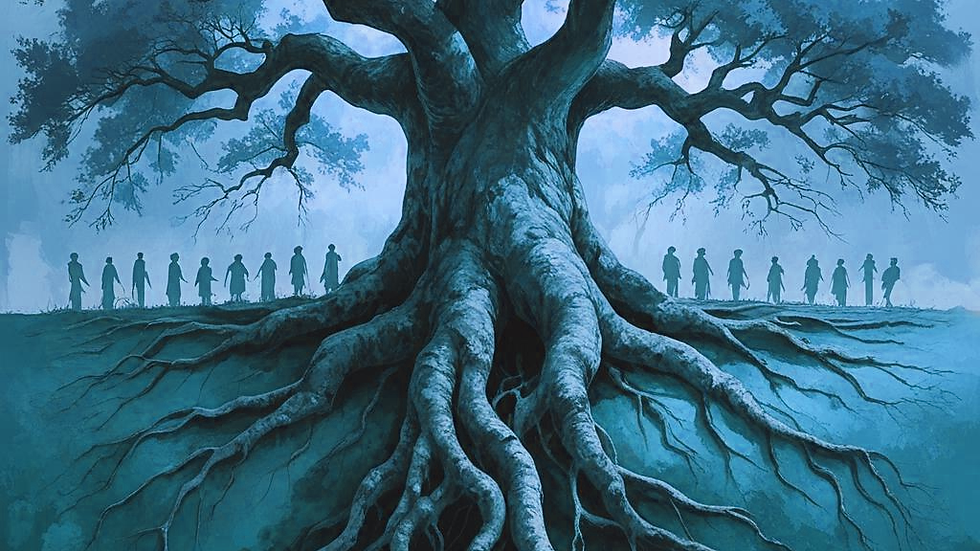

This experience became the seed for a broader inquiry: What if our classrooms, training environments, and team spaces recognized and worked with ancestral memory as a foundational part of human learning, identity, and the workplace? By honoring ancestral memory, we root learning and work in something meaningful, relational, and whole. Classrooms become places of remembrance, not just instruction. Teams evolve into spaces where wisdom is carried, not just performed. And life itself becomes more intelligible, because we’re no longer pretending we arrived here without a story.

"Behind every learner is a lineage. And behind every question is a story."

Below, I offer a framework of four layers of ancestral memory, drawn from both spiritual reflection and educational design, along with practical insights and research-based relevance for anyone teaching or facilitating growth in others.

1. Immediate Generational Memory

“The stories that shaped our dinner tables.” Approximate span: 1–2 generations back (parents, grandparents)

This layer includes family narratives, traditions, values, and adaptive behaviors passed down through generations, sometimes consciously, often unconsciously. Educators and leaders may recognize these patterns in how individuals respond to authority, express emotion, handle conflict, or engage in learning and service. While psychologist Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart identifies the lingering impact of historical trauma, especially within Indigenous communities, others like Dr. Wade Nobles emphasize the lineage-based transmission of cultural excellence, spiritual identity, and communal intelligence. A child might inherit a love of storytelling from a grandparent, just as another may carry quiet survival strategies shaped by generations of hardship.

Whether the family environment was nurturing, complex, or painful, this layer of memory holds the possibility of integration—honoring what uplifts, transforming what harms, and becoming an active bridge for healing or continuation within the lineage. In both educational and workplace settings, this awareness allows us to recognize inherited gifts while gently interrupting patterns that no longer serve.

Relevance in practice: A child who shuts down when asked to present may be echoing a lineage of cultural invisibility or trauma around public speaking. An adult learner who deeply resists failure might carry internalized expectations of survival-based perfectionism from immigrant parents. Conversely, a student who instinctively steps into a leadership role during group work may be drawing on a family tradition of caretaking or organizing community gatherings. In the workplace, an employee who excels at harmonizing group dynamics may unconsciously embody a long-standing family ethos of mediation, hospitality, or relational stewardship.

Educational approach:

Recognize and uplift strengths rooted in family legacy—such as service, leadership, hospitality, or resilience—by naming and integrating them into classroom roles, peer mentoring, or culturally responsive project design.

Invite storytelling in safe formats: journals, oral histories, or digital memory projects.

Use compassionate curiosity when confronting resistance or shame

Allow for pauses, processing time, and reflective rituals when unpacking family narratives

2. Lineage Identity Memory

“The deeper cultural current we were born into.” Approximate span: 3–7 generations back

These are inherited cultural identities shaped by region, religion, race, diaspora, or lifeways; often beneath conscious awareness but evident in worldview, relational patterns, and ways of knowing. For example, a student from the Caribbean diaspora may instinctively avoid direct disagreement, reflecting inherited cultural values of communal respect and relational harmony. A first-generation college student from a working-class Midwestern family may prioritize humility, self-reliance, and a strong work ethic over self-promotion, shaped by generational values of practicality and quiet perseverance. Or an adult learner with Indigenous ancestry might approach tasks through intuitive, non-linear pacing, echoing ancestral lifeways rooted in cyclical time and natural flow.

Relevance in practice: A learner may not speak their ancestral language but still carry its cadence in rhythm, gesture, or artistic form. Lineage memory can surface in a person's intuitive style of problem-solving, storytelling, or conflict navigation. Tewa scholar Dr. Gregory Cajete describes this inheritance as “learning through participation in the story of the people” — a process where ancestral knowledge lives on through daily practice, shared memory, and cultural expression. Likewise, Dr. Wade Nobles, a pioneer of African-centered psychology, frames this as the reclamation of cultural knowledge systems, restoring collective memory that a forced assimilation sought to erase.

Educational approach:

Include cultural epistemologies: Indigenous science, ancestral agricultural methods, African oral tradition, etc.

Honor different rhythms of participation (e.g., call-and-response, circular discussion, silent knowing)

Design with identity, not just learning outcomes, in mind

3. Original Ways Memory

“The memory of how our people once lived, before major cultural disruption, intact systems of wisdom, spirit, and belonging.”

Approximate span: 8–50+ generations back

This memory resides in archetypes, ceremony, ecological knowledge, and precolonial practices, such as druidic traditions before the Romans, indigenous African spiritual system before the slavetrade, or indigenous peoples of the Americas before European colonization. It often returns through dreams, rituals, and symbols, even among those disconnected from traditional knowledge.

Relevance in practice: Students may feel inexplicable comfort around fire, music, or circle gatherings. A workshop participant may be moved to tears by an ancestral instrument they’ve never seen before. These are signs of original ways memory resurfacing through the body and psyche.

Educational approach:

Incorporate ancient symbols, natural materials, or seasonal rhythms into classroom rituals

Create space for silence, intuition, and ancestral dreamwork in personal growth exercises

Respect the sacred; acknowledge that learning can also be remembering

4. Universal Ancestral Memory

“The memory that lives in all of us.” Approximate span: Pan-human and archetypal memory

This is the collective memory shared across all peoples: the fire circle, the migration story, the mother tongue. It surfaces in myth, poetry, spiritual practice, and cross-cultural resonance.

Relevance in practice: This is what allows a student from one culture to feel moved by the art, stories, or ceremonies of another, not through appropriation, but through recognition. It’s why certain archetypes (e.g., the wise elder, the shapeshifter, the healer) show up in every culture. Carl Jung referred to this as the collective unconscious, where archetypes live across time and geography. In learning environments, it appears when something resonates in the “bones” before the mind can explain it.

Educational approach:

Use myth, story, and symbol across cultures to tap deeper human wisdom

Create reflective practices that connect learners to their intuitive sense of truth

Offer cross-cultural connection as a bridge, not a substitute, for rooted identity

✨ Learn More: Free Workshop Series on Ancestral Memory

If this topic speaks to you, I invite you to join me for a free four-part workshop starting July 20, 2025, exploring these layers more in-depth. We’ll explore how ancestral memory lives in our bodies, our classrooms, and our work as healers, leaders, and educators.

Sign up on Meetup or Eventbrite

References

Cajete, G. (1994). Look to the mountain: An ecology of Indigenous education. Kivaki Press.

González, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Jung, C. G. (1969). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (2nd ed., R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1959)

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

Nobles, W. (2006). Seeking the Sakhu: Foundational writings for an African psychology. Third World Press.

Yellow Horse Brave Heart, M. (1998). The return to the sacred path: Healing from historical trauma and historical unresolved grief among the Lakota. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 68(3), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377319809517532

About the Author

Lisa Dawley, Ph.D. is a lifelong educator, technologist, and conscious systems designer. With over $15M in funded research and development, and 30+ years of innovation across edtech, AI, and transformational learning, she now guides soul-centered leaders and learners through her work at Soul Mirror Studio.

Comments